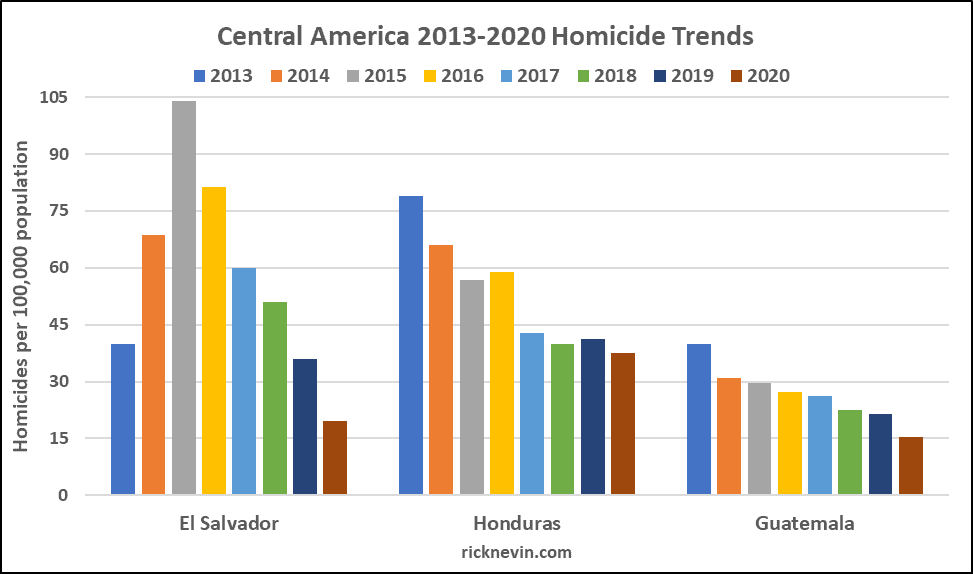

Central America homicide rates are falling fast

In North America and Europe, the phaseout of leaded gasoline occurred over the span of a decade or longer. The phaseout was mostly implemented from the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s in Canada and the USA, and from the mid-1980s through the 1990s in Western Europe. That is why crime in Britain peaked about 10 years after the USA crime peak.

In 1996, the World Bank reported that many nations in Latin America did not begin selling unleaded gasoline until the 1990s, but some also transitioned to 100% unleaded gasoline very quickly. El Salvador began selling unleaded gasoline in 1992 and banned the sale of leaded gasoline in 1996. Honduras began selling unleaded gasoline and banned leaded gas in the same year – 1995. Guatemala banned leaded gas in 1991.

USA homicide trends from 1900-1998 followed earlier trends in lead exposure with a lag of 21 years. If that pattern held in Central America, then we would expect their homicide rates to peak about two decades after their leaded gas bans in 1996, 1995, and 1991.

The El Salvador homicide rate fell 81% from 2015 through 2020. The Honduras homicide rate fell 52% from 2013 through 2020. The Guatemala homicide rate fell 62% from 2013 through 2020.

In South America, Columbia began selling unleaded gasoline and banned the sale of leaded gasoline in 1990. In 1994, air lead levels recorded in Medellin Columbia were 86% lower than levels recorded in 1980. The Columbia homicide rate fell 64% from 2002 to 2020.

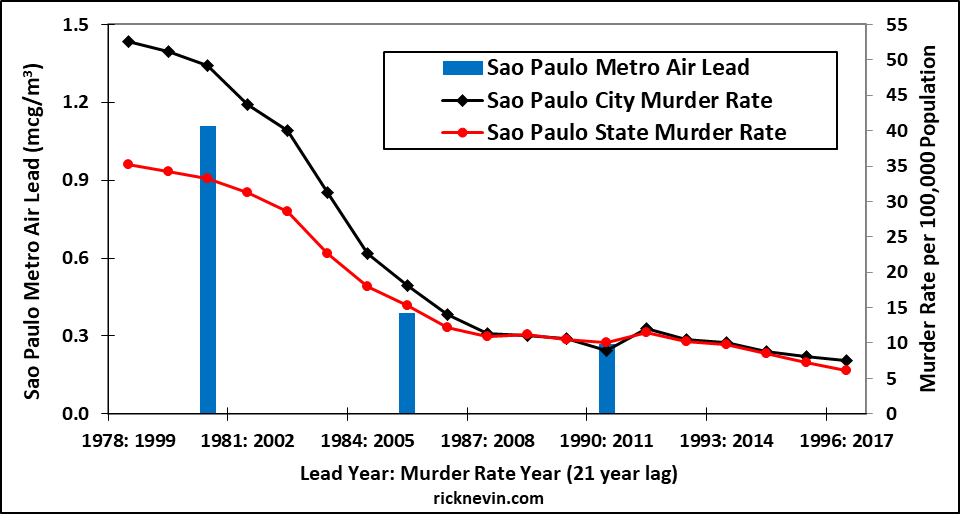

Brazil banned the sale of leaded gasoline in 1991. The homicide rate in Brazil fell 25% from 2014 to 2020, but the Brazil homicide story is really two stories: The Sao Paulo story and the story for the rest of Brazil.

In 2018, the World Economic Forum on Latin America highlighted the astonishing and underreported murder mystery of Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Latin America’s largest city, São Paulo, was once among the region’s most violent. But the bustling metropolis of over 12 million Paulistanos has experienced a remarkable decline in homicide. The murder rate dropped from a high of 52.5 per 100,000 in 1999 to just 6.1 per 100,000 today. The current rate is almost five times lower than the national average. What’s more, most forms of crime declined, albeit more modestly, over the same period.

So what happened?

There are many competing explanations for why São Paulo registered such monumental improvements in safety. …

Whatever the explanation, the city’s great crime drop does not receive much international attention. (Muggah & Szabó de Carvalho, 2018)

Sao Paulo’s great crime drop is explained by Sao Paulo air lead levels recorded in 1980, 1985, and 1990. A 21-year time lag for lead exposure and homicide trends provides a striking visual fit for Sao Paulo declines in air lead levels and murder rates.

Sao Paulo’s air lead decline occurred after 1975, when Brazil began its National Alcohol Program to reduce oil imports. The program initially created ethanol production incentives and required 10% ethanol blending in gasoline. In 1979, the program created incentives for automakers and car buyers to develop an ethanol car market. Sao Paulo state produced the vast majority of Brazil’s ethanol and had the lowest ethanol prices in Brazil due to lower production and transportation costs, causing ethanol use to be concentrated in Sao Paulo.

The 1996 World Bank report also found that some nations in Latin America were still not in any great hurry to ban lead in gasoline. Venezuela was not planning on selling unleaded gas until 1999 and did not expect to ban leaded gas until 2005. Trinidad and Tobago began selling unleaded gas in 1995 but had no plan to ban leaded gas until 2005 at the earliest. Jamaica began selling unleaded gas in 1990 but did not expect to ban leaded gasoline until 2001. In 1996, the market share of unleaded gas was 30% in Jamaica, 10% in Trinidad and Tobago, and zero percent in Venezuela.

Venezuela had the highest murder rate in Latin America in 2017, 2018, and 2019, and the second highest in 2020. Jamaica had the highest murder rate in 2020, the second highest in 2019, and the third highest in 2018 and 2017. Trinidad and Tobago had the fourth highest murder rate in 2019 and 2020, and fifth highest in 2018.