“A black male baby born today … stands a” near-zero chance of going to prison

Bonczar & Beck (1997) estimated the lifetime risk of going to state or federal prison at birth and showed how the remaining risk of going to prison for the first time declines with age, based on the assumption that “incarceration rates recorded in 1991 remain unchanged in the future”. For black males, the lifetime risk was 28.5% at birth and the risk of going to prison for the first time fell to 17.3% after age 25, 6.5% after age 35, and 2.1% after age 45. Those estimates do not apply today because incarceration rates have changed, with younger men recording the largest declines.

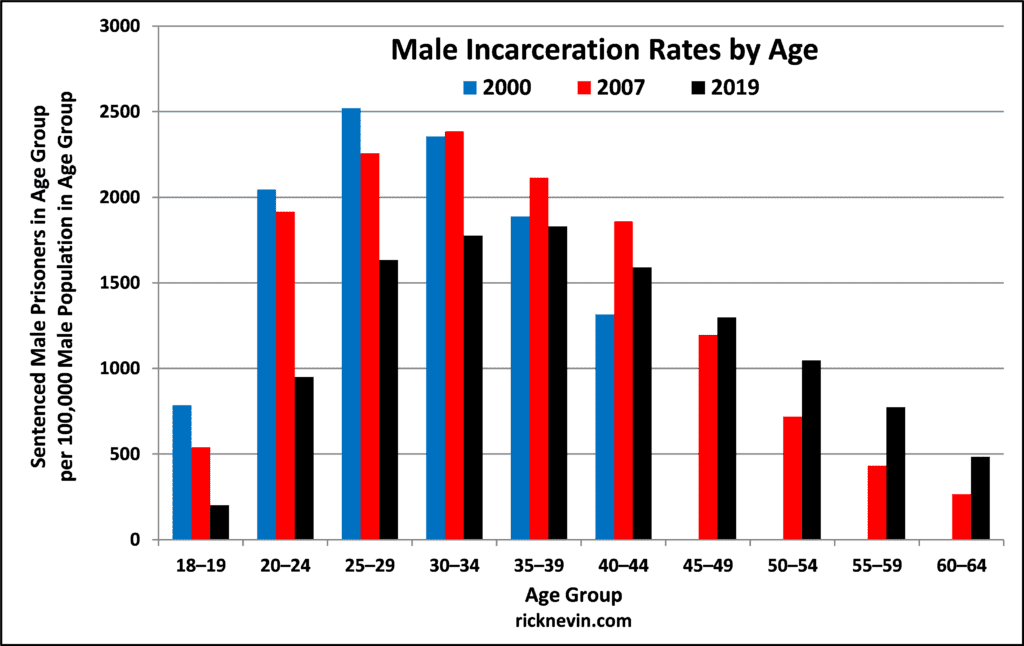

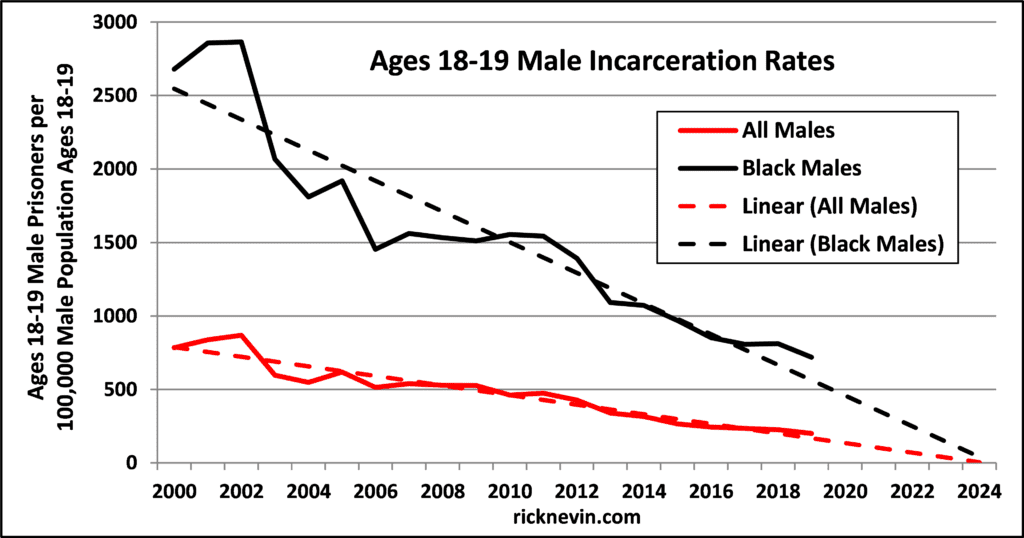

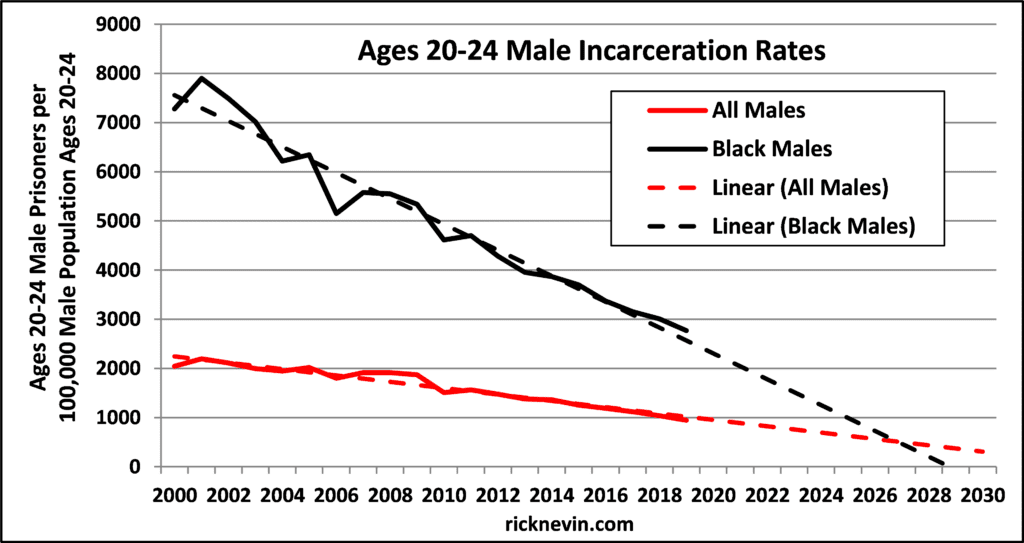

From 2000-2019, male incarceration rates fell 74% for ages 18-19, 54% for ages 20-24, 35% for ages 25-29, and 25% for ages 30-34, but rose 21% for ages 40-44. Data for older age groups, first reported in 2007, show male incarceration rates from 2007-2019 rose 45% for ages 50-54, 79% for ages 55-59, and 82% for ages 60-64. In absolute terms, men ages 25-29 had the highest incarceration rate in 2000 but men ages 35-39 had the highest incarceration rate in 2019.

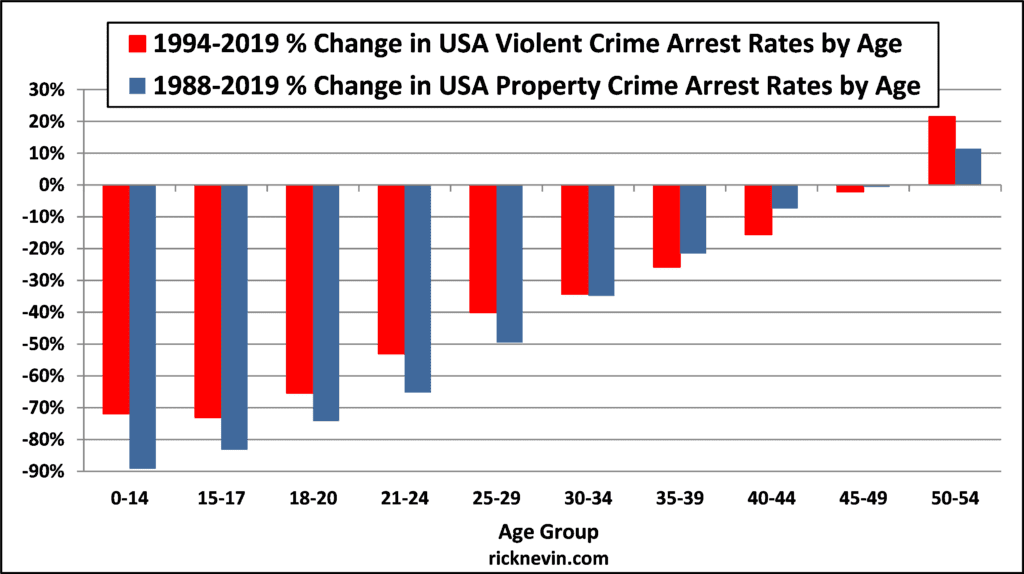

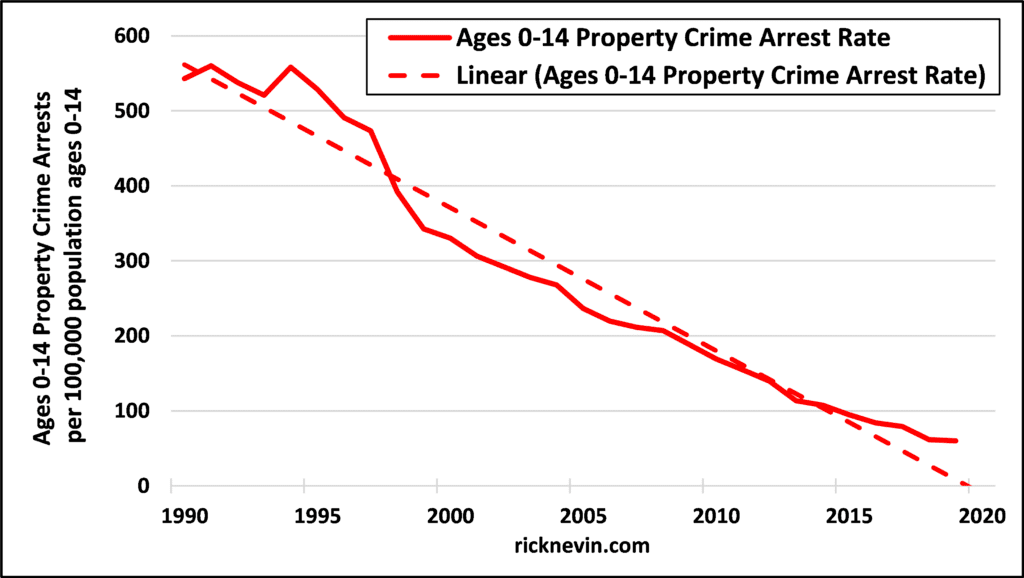

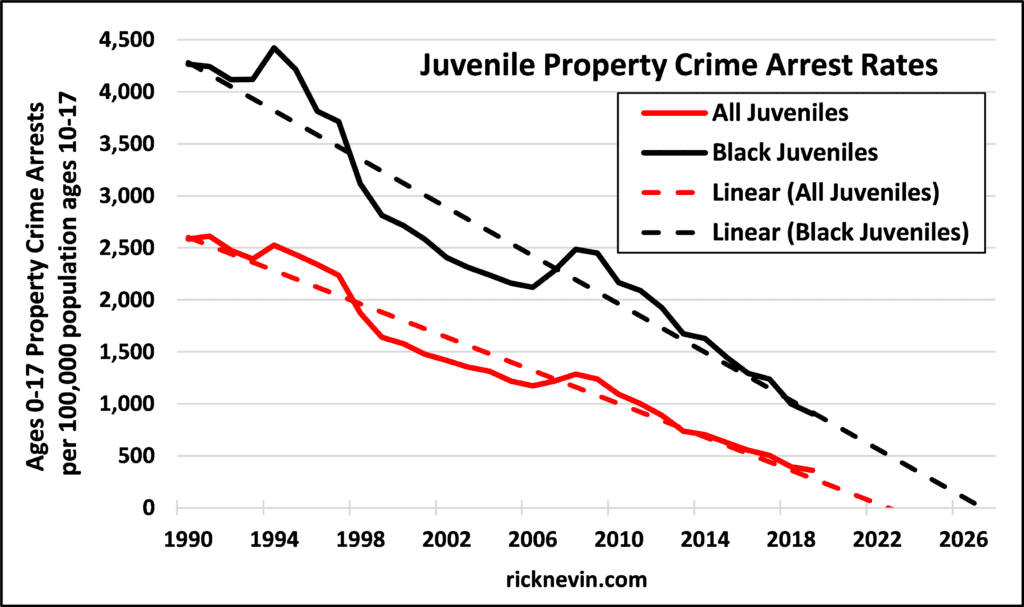

The 2000-2019 change in male incarceration rates reflects ongoing trends in arrests by age. From 1994-2019, violent crime arrest rates fell 72% for ages 0-14, 73% for ages 15-17, and 65% for ages 18-20, but rose 21% for ages 50-54. From 1988-2019, property crime arrest rates fell 89% for ages 0-14, 83% for ages 15-17, and 74% for ages 18-20, but rose 11% for ages 50-54.

Falling juvenile and young adult arrest and incarceration rates and rising rates for older adults are all explained by birth year trends in lead exposure. The decline in juvenile arrest rates through 2019 compares juveniles born after the 1970-2000 decline in lead exposure versus juveniles in the late-1980s and early-1990s, born near the early-1970s peak in leaded gas emissions. The increase in arrest rates for ages 50-54 compares adults in 2019 born near the circa 1970 peak in lead exposure versus adults ages 50-54 in the late-1980s and early-1990s born before the 1945-1970 rise in leaded gas emissions.

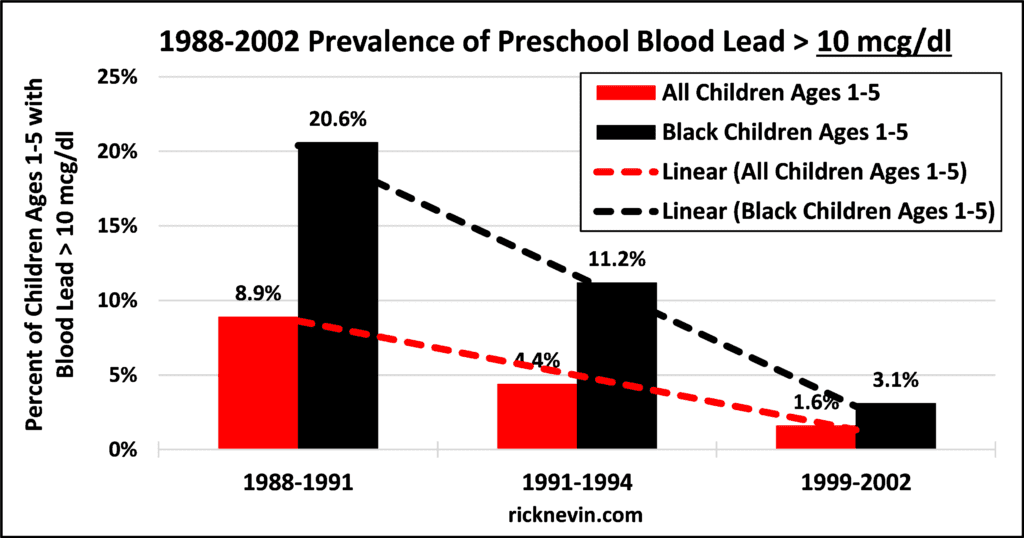

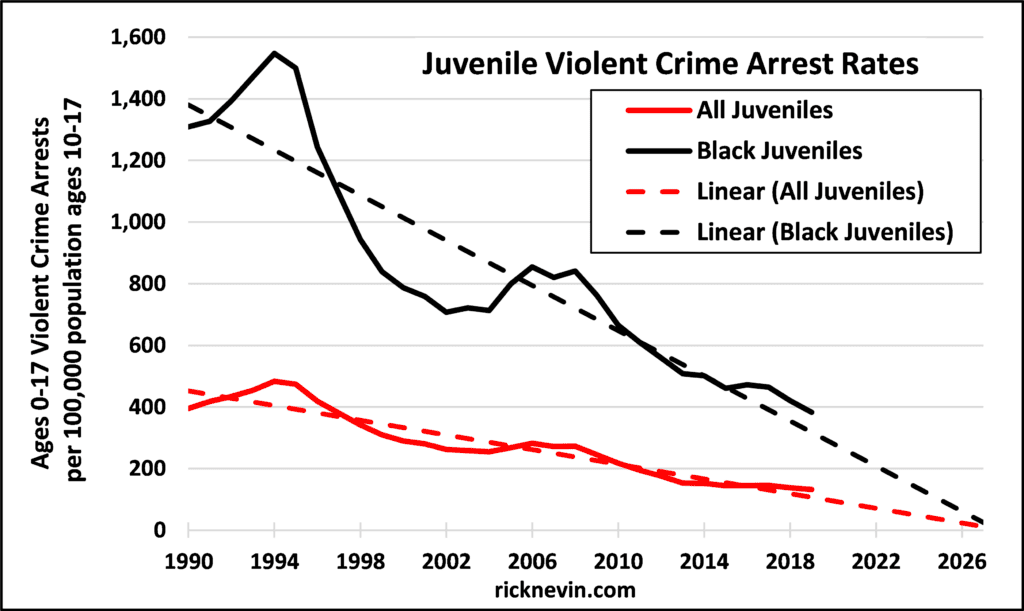

There were extreme racial disparities in preschool lead exposure in the 1960s and 1970s because black children were disproportionately concentrated in old housing with lead paint hazards and in cities with higher air lead due to city traffic. The phaseout of leaded gasoline from the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s sharply reduced racial disparities in severe lead poisoning, and subsequent racial differences in juvenile homicide arrest rates.

“Blood lead prevalence over 30 mcg/dL among white USA children fell from 2% in 1976-1980 to less than 0.5% in 1988-1991, as prevalence over 30 mcg/dL among black children plummeted from 12% to below 1%. The white juvenile murder arrest rate then fell from 6.4 to 2.1 from 1993-2003, as the black juvenile rate fell from 58.6 to 9.7.” (Nevin, 2007)

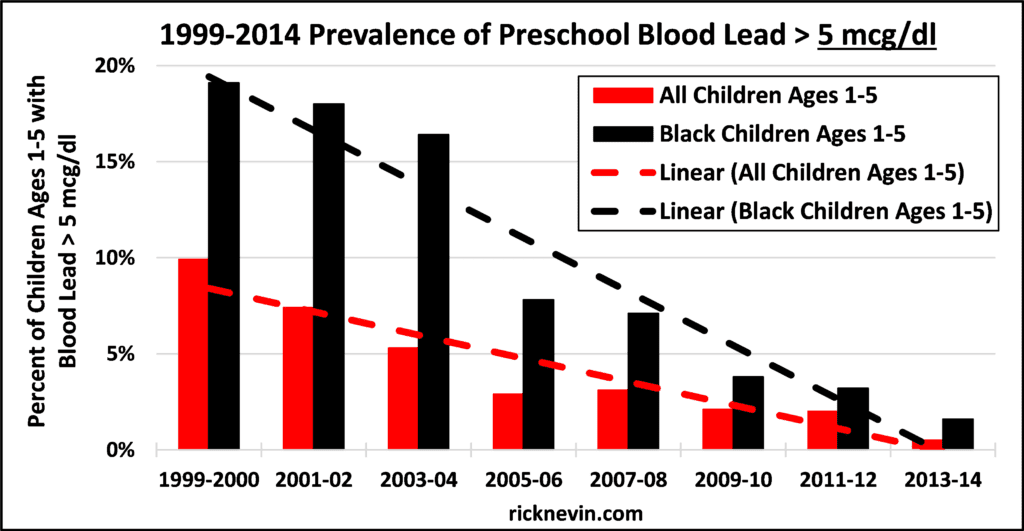

The Residential Lead-Based Paint Hazard Reduction Act of 1992 and other efforts to reduce lead exposure have further reduced elevated blood lead prevalence and racial disparities. Preschool prevalence over 10 mcg/dl fell from 8.9% in 1988-1991 to 1.6% in 1999-2002, as prevalence over 10 mcg/dl among black children fell from 20.6% to 3.1%. Subsequent surveys report 1999-2014 declines in prevalence over 5 mcg/dl and steeper declines in black prevalence over 5 mcg/dl, with both trends converging near zero in 2014.

Wright (2008) found that preschool blood lead above 5 mcg/dl is associated with a higher risk of violent and property crime arrests, and arrest rates rise with each 5 mcg/dl increase in blood lead. We cannot say if there is any increased risk of arrests associated with blood lead lower than 5 mcg/dl or if there is a baseline level of offending associated with zero preschool lead exposure. With every passing year, however, trendlines provide more evidence suggesting arrest and incarceration rates could fall to levels remarkably close to zero if all preschool children had blood lead levels below 5 mcg/dl.

The 1990-2019 linear trend for the ages 0-14 property crime arrest rate hits zero in 2020. That trend should reflect declines in prevalence over 5 mcg/dl through 2005. The Wright study suggests more declines to come in ages 0-14 arrest rates because we have already recorded ongoing declines in prevalence over 5 mcg/dl from 2005 through 2014.

Black juvenile arrest rates are also converging with overall juvenile arrest rates, consistent with the earlier racial convergence in elevated blood lead prevalence. Violent crime arrest rates for all juveniles and black juveniles are on track to converge near zero in 2026.

The overall juvenile property crime arrest rate trendline hits zero in 2023 and the black juvenile property crime arrest rate trend hits zero in 2027. In 2019, the black juvenile property crime arrest rate was less than 35% of what the overall juvenile property crime arrest rate was in 1991.

The same convergence pattern is evident in 2000-2019 prison incarceration trends. Incarceration rates for all men ages 18-19 and for black men ages 18-19 are on track to converge near zero in 2024. The incarceration rate trendline for all men ages 20-24 hits zero in the early 2030s and the trendline for black men ages 20-24 hits zero in 2029.

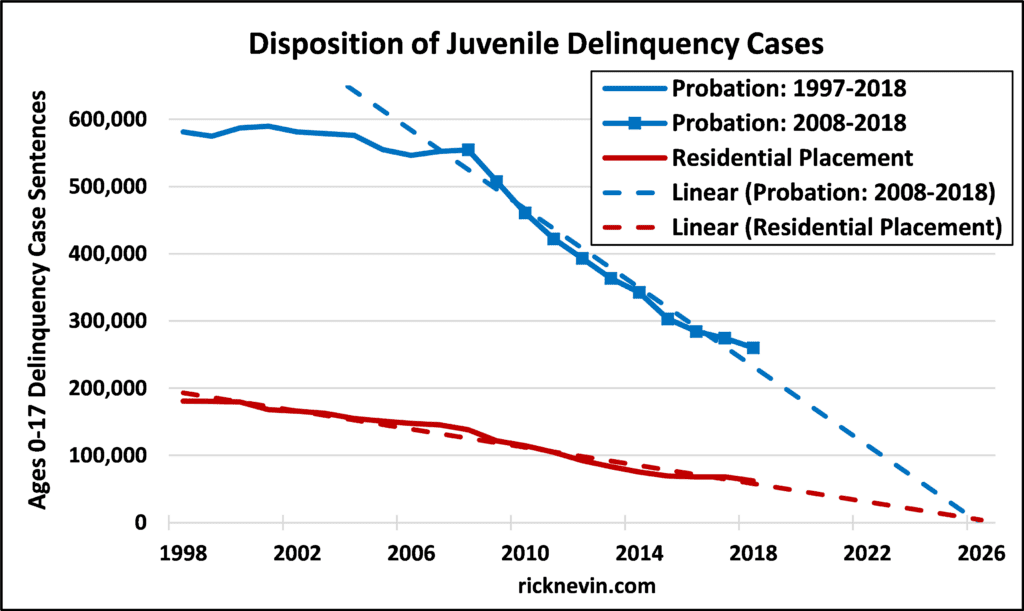

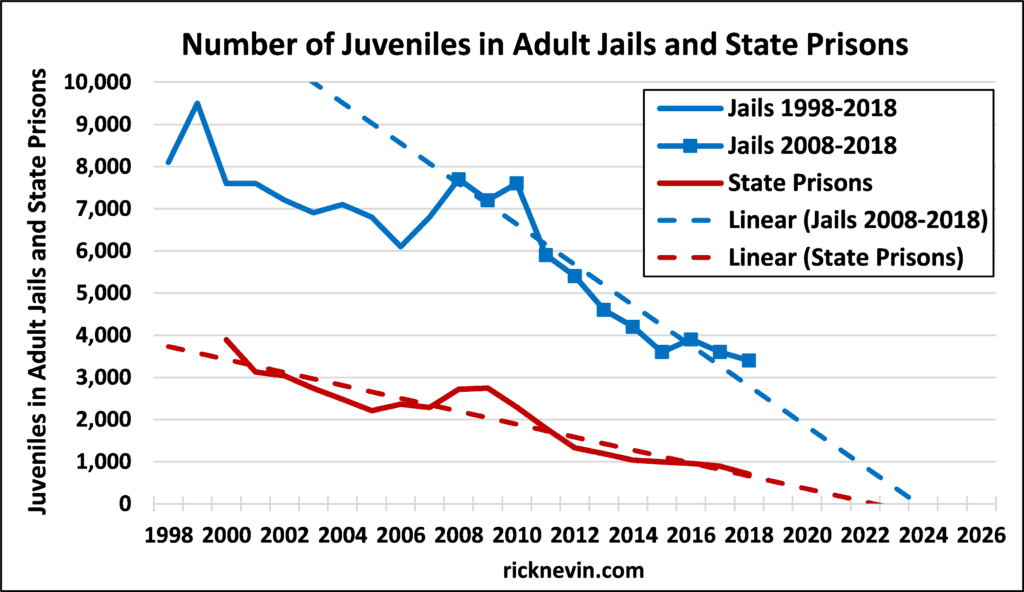

Bonczar & Beck found that almost two-thirds of those admitted to prison for the first time have served a prior sentence to probation and a third have served a sentence in an adult jail or juvenile residential placement (corrections) facility. Probation, jail, and juvenile residential placement are the “pipeline to prison”. That pipeline is running dry.

The number of juveniles sentenced to probation peaked at 604,800 in 1997, fell by 8% from 1997 through 2008, and fell at a steeper rate from 2008-2018, on track to hit zero in 2026. The number of juveniles sentenced to residential placement peaked at 180,600 in 1998 and fell to 62,100 in 2018, on track to hit zero in 2026.

The number of juveniles in adult jails peaked at 9,500 in 1999, fell 19% from 1999-2008, then fell at a steeper rate from 2008-2018, on track to hit zero in 2024. The number of juveniles in adult state prisons fell from 3,892 in 2000 to 699 in 2018, on track to hit zero in 2022.

Mendel (2014) observed that “juvenile justice officials and some advocacy organizations have tried to claim credit” for declining juvenile incarceration, “chalking up the progress to their own policies and practices.” While he agrees that some reforms have made a difference, he questions whether national trends can be attributed to reforms that “remain the exception in juvenile justice, not the rule.” Mendel cited research showing “virtually no change in youth incarceration as a share of total delinquency cases” from 1995-2009, and a National Council on Crime and Delinquency study that found “youth adjudicated delinquent were actually more likely to be placed into correctional or other residential facilities in 2012 than in 2002.” In summary, Mendel quotes a Casey Foundation finding that “it is less clear whether [recent trends in youth confinement] reflect a genuine de”incarceration movement, or rather signal that this is an opportune time to start one.”

With juveniles sentenced to probation and residential placement on track to hit zero in 2026, and juveniles in adult jails on track to fall to zero in 2024, the pipeline to prison for men ages 18-19 will run dry sometime around 2024-2026. From this perspective, it is not surprising that the incarceration rate for men ages 18-19 is on track to hit zero in 2024.

In addition to the fall in juveniles on probation and in adult jails, the number of adults in jail fell by 5.5% from 2008-2018 and adults on probation fell by 18% from 2007-2018. This further reduces the number of young adults most likely to go to prison for the first time in their early-20s. The large incarceration rate decline for men ages 18-19 will also reduce the number of men going to prison for a second time in their early-20s. From this perspective, it is not surprising that the prison incarceration rate for males ages 20-24 is on track to hit zero by sometime around 2030.

The National Institute of Justice (2014) reports that only 10% to 30% of criminals start offending after adolescence, so the vast majority of adult offending is done by adults who started offending as juveniles. This means that steep declines in juvenile arrest rates will inevitably cascade through older age groups over the next few decades as the worst years of preschool lead exposure recede into the past, ensuring a long-term decline in crime.

Bonczar (2003) updated the estimated lifetime risk of going to prison, raising the risk for black males to 32.2% based on the assumption that “age-specific rates of first incarceration remain at 2001 levels”. That “stale statistic” was echoed in a 2013 report on racial disparities in the criminal justice system and in headlines stating “1 In 3 Black Males Will Go To Prison In Their Lifetime”. It was also repeated by a 2015 candidate for President stating: “A black male baby born today, if we do not change the system, stands a 1 in 3 chance” of being incarcerated. That “1 in 3” risk estimate was not accurate in 2013, or in 2015, and is even less accurate today. Trends in preschool lead exposure, arrest rates by age, and “age-specific rates of first incarceration” suggest that the lifetime risk of going to prison for any child “born today” could be shockingly close to zero.

In the current debate over criminal justice reform, there are “tough-on-crime” advocates on one side who are concerned that changes made in the name of “reform” could lead to a resurgence in crime. That is not possible. Criminal offending almost always begins with juvenile offending, so there is no chance the USA will see any enduring resurgence in crime unless and until there is a resurgence in offending by juveniles and young adults. On the other side of this debate are reform advocates inclined to claim credit for the fall in the USA incarceration rate over recent years, attributing that fall to their success in implementing reforms. This claim does not seem at all credible, unless there is some criminal justice reform that can explain massive declines in juvenile and young adult arrests and incarceration while arrest and incarceration rates rise for older adults. In summary, it seems clear that declines in the overall USA incarceration rate do not reflect the impact of criminal justice reforms but do signal that this is an opportune time to enact such reforms.